Who coined NewLaw?

I am often asked, ‘Who coined NewLaw?‘. For the record, here are the facts set out in a non-revisionist account of the circumstances from 2009 to 2016.

Contributions to deepen or set the record straighter are most welcome.

2009

Thanks to my friend Friedrich Blase, we know that in the Kerma Partners Quarterly, Issue 2 of 2009 Michael Huber wrote  an article on The Emergence of “NewLaw” (Note: Michael wrote the neologism as one word with a capital ‘L’). Regrettably, the online page no longer exists but, courtesy of Friedrich, here’s an extract from the print edition that clearly shows Michael was onto the idea of a new business model as an alternative to that of traditional law firms.

an article on The Emergence of “NewLaw” (Note: Michael wrote the neologism as one word with a capital ‘L’). Regrettably, the online page no longer exists but, courtesy of Friedrich, here’s an extract from the print edition that clearly shows Michael was onto the idea of a new business model as an alternative to that of traditional law firms.

“My belief is that there are a number of cross-industry views and best practices that can be utilized and applied to the NewLaw model starting with:

Managing the talent pipeline through the use of critical behavior interviewing and critical success-factor filtering, which also has the potential benefit of significantly reducing turnover and improving the retention of top performers.

Employing more of a project-management approach to estimating, managing and delivering successful outcomes, including a staffing process that reflects a more efficient way to achieve the desired outcomes and provides better associate satisfaction.

Utilizing more business acumen and intelligence to understand and deliver on the economic value added by the firm’s services.

New operational metrics to supplement the traditional backward-looking ones to provide a better sense of changes to supply and demand.

New points of view, new perspectives, new market offerings, new tools, new ways to manage — NewLaw.”

Michael cited Fred Bartlit’s Bartlit Beck (a breakaway from Kirkland & Ellis) and Pat Lamb’s Valorem Law Group (a breakaway from Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP) as examples of firms adopting these ‘new’ strategies. Clearly, Michael Huber was thinking of what I would now call ‘remade’ BigLaw (vide infra) firms.

Note: Michael Huber did not refer to non-lawyer ownership or external capital as dimensions of a NewLaw firm.

2010

The late and much loved Professor Larry Ribstein wrote ‘The Death of Big Law‘ in issue 749 of the Wisconsin Law Review. Larry Ribstein’s summary reads:

“Large law firms face unprecedented stress. Many have dissolved, gone bankrupt, or significantly downsized in recent years. This Article provides an economic analysis of the forces driving the downsizing of Big Law. It shows that this downsizing reflects a basically precarious business model rather than just a shrinking economy. Because large law firms do not own durable, firm-specific property, a set of strict conditions must exist to bind the firm together. Several pressures have pushed the unraveling of these conditions, including increased global competition and the rise of in-house counsel. The large law firm’s business model therefore requires fundamental restructuring. Combining insights from the theory of the firm, intellectual property, and the economics of legal services, this Article discusses new models (emphasis added) that might replace Big Law, how these new models might push through regulatory barriers, and the broader implications of Big Law’s demise for legal education, the creation of law, and lawyers’ role in society.”

Professor Ribstein was referring to the business model of large traditional law firms, hence Big Law (two words, both with first letters as capitals), but he was anticipating new corporate structures. Significantly, this paper did address, inter alia, outside ownership and the utility of external capital.

Note: Larry Ribstein gave me the idea of using ‘BigLaw’ as short-hand for the business of traditional law firms of any size, not just the large and most visible ones.

6 September 2013

On 6 September 2013, I wrote Last days of the BigLaw business model which explained how the BigLaw business model is built on six elements:

- Attraction and training of top legal talent,

- ‘Leveraging’ of these full-time lawyers to do the bulk of the work serving clients,

- Creation of a tournament to motivate the lawyers to strive to become equity partners (the idea of a tournament is akin to Roman gladiator contests and the subject of the seminal book, Tournament of Lawyers, 1991).

- Tight restriction on the number of equity owners,

- Structuring as a partnership, and

- Charging high hourly rates (which is or at least until very recently has been possible because of the mystique associated with legal advice).

I opened this post:

“As recently as a few days ago, The Lawyer in London published a range of prognostications about the shape and fate of large law firms in 2018. For partners in large law firms the articles don’t make entirely comfortable reading.

But, The Lawyer, like almost all law firm leaders and observers of large law firms, misses the real point. The reality of 2018 and beyond will turn out to be a great deal worse and much more varied than The Lawyer suggests. And the adversity applies to all law firms not just big ones. Here’s why.

‘BigLaw’ is not about big law firms. It’s description of the business model used by firms generating more than 99% of law firm revenues today (that is, it excludes micro and sole practitioner ‘firms’ and the handful of alternative business model firms).

Let me explain by starting with a little history. In 1819 the firm we know today as Cravath Swaine & Moore LLP was founded in New York. Early in the 20th Century Paul Cravath enunciated the principles of a system to train associates rigorously and promote exclusively from within. To quote the firm’s website: “The rotation path fosters collaboration and eliminates the need for associates to compete for work, clients, training or bonuses. The Cravath System places a premium on efficiency and quality of work that no other firm matches, and it was through this value system, which we still use today, that Cravath created a new model for American law firms.”

One should add what Paul Cravath really invented was the foundation for the contemporary BigLaw business model. The modest claim to be “a new model for American law firms” is insufficient. The model rapidly became the basis of the Magic Circle and White Shoe firms – and every other law firm that strives to learn from and emulate the model.

In the great industrial boom of the post World War II era firms seized on the Cravath model and turned it into the BigLaw model. The BigLaw business model enabled the massive growth of firms throughout the Anglo-American world – and has generated the fabled incomes of the equity partners of BigLaw firms for more than 60 years.”

Note: I had coined ‘BigLaw’ as a way of describing the business model of traditional law firms about which Michael Huber and Larry Ribstein had written in 2009 and 2010, respectively. The idea was to have s short-hand mnemonic way of describing the business model of traditional firms, BigLaw, and that of the newcomers, NewLaw.

13 September 2013

On 13 September 2013, a member of our firm, Eric Chin, wrote 2018: The year Axiom becomes the world’s largest legal services firm. Based on their respective CAGRs of that time, Eric’s post speculated Axiom Law would overtake DLA Piper within five years, i.e. by 2018, as the world’s largest provider of legal services.

To find a collective noun for legal services providers like Axiom, Eric used NewLaw in his post. We both believed he had coined a neologism:

“The meteoric rise of substitutes (in the Michael Porter sense) for traditional BigLaw firms is witnessing the emergence and growth of firms like Axiom Law, Riverview Law, Keystone Law, AdventBalance, to name but a few. To describe these substitutes I have coined the collective noun ‘NewLaw’ (emphasis added). These firms are designed around virtual work spaces and rely on the rise of super temps. Supertemps are lawyers who have

been trained by traditional BigLaw firms who are now looking for flexible work arrangements. These alternative business model (ABM) legal services providers are able to provide the same or similar service levels to BigLaw – but at or below incumbents’ break-even points.”

Note: Eric Chin (and I) thought he had invented NewLaw, unaware of Michael Huber’s earlier paper.

7 October 2013

Nearly four weeks later on 7 October 2013, I wrote The rise and rise of the NewLaw firm business model.

Within hours of posting The rise and rise of the NewLaw firm business model, my friend Joel Barolsky provocatively opened the batting in the Comments:

“Personally, I think you underestimate the strength and resilience of BigLaw and overstate the competitiveness of NewLaw. My view is based on 6 factors:

1. Semi-variable cost structure

2. Deal-driven profit – cyclical not structural

3. Globalisation – net impact is low for most

4. Labour arbitrage

5. Fixed pricing and efficiency dividend open to all

6. Reap and sow.”

As the first to comment, Joel set the tone, no doubt provoking both the many protagonists and antagonists who followed.

In just four weeks, by November 4, I received nearly 25,000 words of Comments and Replies contributed by over 40 people from many corners of the globe.

The maelstrom was described by Richard Susskind as “a rapid-fire Socratic exchange…in the best spirit of peer production”.

15 December 2013

Pu blication of NewLaw New Rules

blication of NewLaw New Rules

No one can readily comprehend such a long and intricate thread. So with the help of Dr. Imme Kaschner and Eric Chin and the permission of 35 of the contributors, I turned the thread into an e-book, NewLaw New Rules – A conversation about the future of the legal services industry.

On December 15, 2013, we published NewLaw New Rules on Amazon and Smashwords, just over five weeks after closing the Comments.

NewLaw New Rules was beautifully illustrated by Julian Jones; he used the metaphor of the flapping of a butterfly’s wings in the Amazon rain forests causing a tornado in Texas. Richard Susskind kindly wrote the Foreword.

NewLaw New Rules was beautifully illustrated by Julian Jones; he used the metaphor of the flapping of a butterfly’s wings in the Amazon rain forests causing a tornado in Texas. Richard Susskind kindly wrote the Foreword.

Throughout we sprinkled Tweets gathered during the “rapid-fire Socratic exchange” to capture the energy we had unleashed (see two of these Tweets above).

7 February 2014

Aftermath: ReInvent Law, New York City

Aftermath: ReInvent Law, New York City

On 7 February 2014, at the ReInvent Law conference in New York City among the 800+ delegates, I was privileged to meet many of the contributors to NewLaw New Rules. Somewhat ironically they each kindly signed a physical copy.

This electrifying one-day event was a fitting form of e-launch of NewLaw New Rules; my thanks to Professor Dan Katz @computational, one of the organizers.

December 2015

In anticipation of the publication of Remaking Law Firms, I launched a blog, Dialogue on Remaking Law Firms. Dialogue has evolved to a multi-author global forum for those invested in BigLaw firms to add their voices to the remaking conversation.

March 2016

Finally, Remaking Law Firms

Finally, Remaking Law Firms

In the ensuing two years with Imme Kaschner as my co-author, I researched and wrote Remaking Law Firms; Why & How.

Our book was published in March 2016 by the American Bar Association. It received critical acclaim and is being widely read.

In part Remaking Law Firms was a rejoinder to NewLaw New Rules and in part my answer to those BigLaw leaders who challenged me, saying “Now that you’ve scared the ‘s…’ out of us, what the ‘f…’ do we do?”

Imme and I concluded their glasses are half-full and many opportunities are open to all who remake their firms.

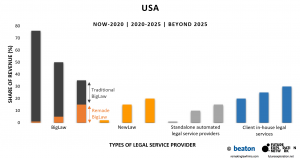

A month later, Ben Farrow and Ross Dawson and I published the first evidence-based on projections of market share in the legal services supply chain, Why BigLaw firms must start remaking their business model now… “and by implication, the consequences of not doing so.” The

A month later, Ben Farrow and Ross Dawson and I published the first evidence-based on projections of market share in the legal services supply chain, Why BigLaw firms must start remaking their business model now… “and by implication, the consequences of not doing so.” The

Delphi forecast was based on the views of 21 contributors from Australia, Canada, England & Wales, US and Western Europe. Many from BigLaw firms requested anonymity.

In summary, Who coined NewLaw?

- Michael Huber was the first to use NewLaw spelled as one word with a capital ‘L’. Michael was writing about ‘new points of view, new perspectives, new market offerings, new tools, and new ways to manage’ in traditional law firms; he did not directly address any fundamental changes in their underlying business model. (2009)

- Eric Chin was the first to apply NewLaw to a business model diametrically different to that of traditional law firms. Eric did so in the context of our team using the term BigLaw firms to characterize the business model of traditional firms. (September 2013)

- George Beaton teased out the BigLaw–NewLaw differences and popularized NewLaw in his multi-contributor e-book NewLaw New Rules, thus enshrining the term in the world-wide lingua franca of legal services. (October 2013)

At the end of the day, who coined NewLaw doesn’t really matter. What’s important is the delivery of legal services now has an increasing diversity of providers and is blessed with rampant innovation which will benefit consumers with access to justice.

In July 2021 Stephen Mayson wrote ‘Is the BigLaw business model sustainable?’ – a milestone article in his blog ‘An independent mind’ *.

This is such an important contribution that it prompts me to re-open Dialogue on Remaking Law Firms and place it in this repository.

Stephen’s analysis addresses what we mean by ‘BigLaw’, ‘business model’ and ‘the BigLaw business model’.

To paraphrase him, The short and long answers are the same: it doesn’t look like the BigLaw business model is sustainable.

I salute your analysis and opinion Stephen. May the dialogue continue.

* https://stephenmayson.com/2021/07/26/is-the-biglaw-business-model-sustainable/