Classic: Technology and the future of the law

Technology and the future of the law is published as a Classic on Dialogue on Remaking Law Firms in early March to coincide with our 2018 Client Choice Awards. You may know that Neota Logic is the sponsor of the Law Firms category in the Awards.

I’ve designated Technology and the future of the law a Classic because Michael’s message and argument are so true as the passage of time is proving – and yet the evidence is that the large majority (perhaps as much as 85%, in Bill Henderson’s rendition of the innovation of diffusion curve below) of law firms are not listening.

A forecast in four acts

One of us Neota Logicians recently joined compatriots from the innovation wing of the legal tech industry to talk (and even think) about the likely effects on law practice of what we all do— build smart and potentially radical software. The forum was ILTA 2014, this year’s edition of the vast and collegial conclave of IT, KM, PM, ED, and other mavens from around the country and the world.

Our compere, Ryan McLeod of Norton Rose Fulbright and the Three Geeks & A Law Blog, brought us together under the banner Do Robot Lawyers Dream of Billable Seconds? We don’t read much science fiction here at Neota Logic, but we do go to the movies and know what Los Angeles will be like in 2019.

Our fellow troublemakers were: Joshua Lenon of Clio (@JoshuaLenon); Noah Waisberg of DiligenceEngine (@DiligenceEngine); and Stuart Barr of HighQ (@HighQ).

Each of us had a rather different viewpoint, perspective, and forecast, so readers should read these terrific posts: Stuart’s What Will Law Firms of the Future Look Like?, Joshua’s Four Visions of The Future of Law, and Noah’s More Efficient Future, Fewer Lawyers?. There is also a Storify roundup of the session thanks to Robert Richards, @richards1000.

So, what’s Neota Logic’s view?

Well, yes, in some future robots will have taken their seats in our offices, frictionless communication will have us wired to our clients in symbiotic synapses, and dumb jobs will all be done by smart tools.

Here at Neota Logic, we write software with which lawyers can build their own robots. (Other legal process applications too, but we’re talking Android Dreams today.) You might say our business is building robots and destroying dumb jobs—the ones lawyers don’t do cost-effectively at scale, and really don’t or shouldn’t want to do.

However, today, we’d like to back away from the edge and reflect a bit on where the profession (yes, it’s still that, in part) is today, where it aims to be tomorrow, and why getting from here to there is so hard.

The averages of law

Despite all that the many, many creative minds at ILTA have done, are doing, will do soon, the profession, on average, across the board, is just here:

—except the secretary has been deaccessioned, or reassigned to attend to five lawyers.

Two data points.

In the year 2012, the American Bar Association’s Committee on Ethics 20/20 announced with great fanfare a new rule of professional ethics—computers exist, email works, lawyers should know these things.

To maintain the requisite knowledge and skill, a lawyer should keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology, engage in continuing study and education …. (emphasis added)

Even ILTA, in its recent and excellent Future Horizons report, isn’t seeing very far ahead. These are the tech futures the profession is told to attend to:

- cloud solutions

- social media tools and analytics

- personalized displays

- collaborative document and knowledge management

- courtroom dashboards

- gesture recognition

- finger tracking

- the intelligent Web

- remote presence

- 5G communications.

If these are the future of legal technology, then what’s an iPhone, which already does all these things? Except courtroom dashboards.

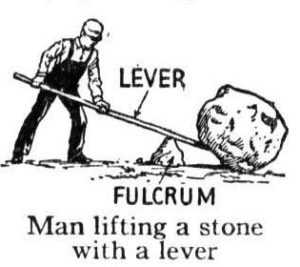

Alas, the profession on average is here—just discovering that “leverage” can mean more than the ratio of partners to associates. And the profession is here—puzzled by the new-fangled inventions of the hard-working inventors all around ILTA, unsure whether to flip a switch or light a match.

The profession would like to be here, if only for the sake of style.

As D. Casey Flaherty (@DcaseyFlaherty) and others have asked, why should this profession be immune to the forces that have transformed far bigger industries?

Robots build cars. Robots drive cars. Computers win hard games. And their power is accelerating and their cost decreasing. Unlike those of lawyers. Last month’s example: IBM’s Neurosynaptic Chip: 1/10th of a watt, 4096 cores, 256 million synapses.

Why is this profession so slow?

We are indebted to Professor Bill Henderson of Indiana Maurer Law School (@wihender) for introducing the legal profession to the Rogers Diffusion Curve, which grew, so to speak, out of research on how, why, and how rapidly the use of hybrid seed corn—invented in Iowa—spread among farmers.

Professor Henderson has some well-researched, economics-based explanations for the legal industry’s generally weary climb up and along the diffusion curve. We leave the hard stuff to him – and encourage you to read his work.

A theory about the void

But we do have a theory, though it may not meet the Niels Bohr test —”Your theory is crazy, but it’s not crazy enough to be true.”

Capital, taxes, and partnerships are the usual suspects. Firms can’t raise capital, taxes are at income rates on current earnings, and partnerships force distributions.

We think the suspects are innocent, or at least only accessories after the fact.

Legal services innovations are not capital intensive by the standards of most industries. Choose the most innovative legal service idea you know of—for example, the projects that law firms submitted for the ILTA Innovative Firm and Project of the Year awards—and count up the investments. A little software, maybe a little marketing, and certainly a lot of brain power. But no trucks, towers, or turbines.

And when law firms do want to invest—as they do on a generous scale when building offices, opening branches and acquiring laterals—they have no difficulty rounding up the cash.

Nope, capital isn’t the problem.

Next defendant: law firms don’t innovate because the partners’ income is taxable when earned by the firm. No retained earnings to plow back into the business. No capital gains.

True, but taxes as a barrier to innovation is a reworking of the capital argument. And we don’t buy that.

And last: law firms don’t innovate because they are partnerships.

Now we’re getting closer to the bone. And right at the bone, after you scrape away the fat, muscle, and blood with your scalpel, is the partnership’s method of dividing profits, often called “the compensation scheme.”

Here’s a taxonomy of schemes, which one management consultant to law firms said is exhaustive: every firm does one of these, perhaps with a wrinkle or tuck.

- Equal Shares

- Lock Step

- Modified Hale & Dorr (the Finder, Minder, Grinder Formula)

- Simple Unit Formula

- 50/50 Subjective/Objective

- Firm + Practice + Individual

- Eat What You Kill

All have their pluses and minuses, as the cliché has it. However, and essential for the discussion today, all but two of these, all but the first two, are tightly tied to hours … yes, to billable hours.

Out of fashion, some say. Certainly, the pundits say. And some clients too. But ask your pricing director (or general counsel) friends, over a beer, for an honest answer to the question, “What percentage of your firm’s revenue (or law department’s spend) is on work that is priced on a basis that is unrelated to hours worked?”

As to “alternative fee arrangements,” the acronymic AFA’s, all of them except the first and last … are still based on hours:

- Fixed

- Phased

- Collared

- Holdback

- Blended rate

- Contingent

- Value-based.

Here’s the traditional method of calculating what is for partners the magic number, the one that shows up in the AmLaw 100 and 200 lists. This is David Maister’s old formula, which was engraved on a gold tablet and bolted to the wall at the ABA headquarters in Chicago.

NIPP = (1 + L) x BR x U x R x M

NIPP = (1 + L) x BR x U x R x M

Net Income Per Partner =

(1 + Leverage)

x Blended Billing Rate

x Utilization: Average Hours Per Lawyer

x (Realization: Revenue/Standard Value: Posted Rates)

x (Margin: Total Profit/Revenue)

Notice the critical factor Utilization—average hours per lawyer. The more hours worked, the higher partner income. Simple.

But, the elephant in the room is stamping and snorting and must be heard.

Innovation destroys hours

Now, that’s bad wherever the majority of lawyers’ revenue is rates x our hours. Every hour saved is a dollar lost.

But it’s especially bad for law firms, and that is almost all of them, whose partner comp schemes set the income of individual partners with a formula that counts the individual partner’s hours, or the hours of her team. Because then she knows that she will be personally penalized for her own innovations.

Firms with equal or lock-step comp (among the Global 100, that’s just a handful) are better off. They can make collective decisions to innovate, to step away from the bar (one step at a time, not 12) away from addiction to the billable hour—and let partners experiment.

The root cause, of course, is the billable hour. But, our crazy theory, which as Niels Bohr said may not be crazy enough to be true, is that partner compensation schemes are a critical obstacle, and one that can, by creative tinkering, be dealt with. For example, by properly accounting for the costs of revenue. What law firms tend to do, instead, when they get what they (and their accounting systems) still regard as “unusual revenue,” whether it’s a fixed fee for a transaction or a subscription fee for an online service, is to flail around and end up under-compensating the entrepreneurial partners.

Innovations, after all, are intended to produce more profit, not less. That’s how real businesses look at it:

Software companies and publishers look for high volume and decreasing marginal costs. Law firms built on billable hours, and constrained by the limitations of the human species, are stuck with constant marginal costs: the next hour costs as much to deliver as the one before it. So volume doesn’t increase margin. (Associate/partner leverage does, but in most BigLaw that can be pushed up only to a diminishing limit.) Indeed, some would say the law firms’ revenue per unit actually declines a bit to the right, so the picture is even worse.

Moreover, again constrained by the species, lawyers cannot work around the clock every day all year long. Airlines look to keep all the seats filled, all their assets earning, at all times. Imagine if airlines said those gigantically expensive airplanes would only be flown during “normal working hours.” Why should law firms leave their most valuable asset—the expertise of their lawyers—unused for two-thirds of the week?

So, we suggest to law firms that a useful, innovation-driving business goal should be:

Leverage without associates and bill without hours

That’s the view from Neota Logic. And that’s what we enable lawyers to do.

Author

Michael Mills is Co-Founder & Chief Strategy Officer at Neota Logic Inc, a leading global provider of intelligent software and provider to many leading law firms and a world authority on artificial intelligence in law.

Michael Mills is Co-Founder & Chief Strategy Officer at Neota Logic Inc, a leading global provider of intelligent software and provider to many leading law firms and a world authority on artificial intelligence in law.

This post was first published on the Neota Logic blog on September 5, 2014.

Leave a Reply