Casey continues, Any story about the lack of change in the legal market premised solely on lawyers being stupid has limited explanatory power. I’m partial to a more nuanced narrative where the incentives to change are not evenly distributed. More specifically, those with the most power, by definition, encounter the least pressure to embrace innovation.

A Primer On The Legal Economic Landscape

For context. Legal Business just released the Global 100 under the banner Hitting the Wall. The headline for this year’s Am Law 100 was Signs of a Slowdown. The Altman Weil 2016 Law Firms in Transition survey opens with the observation that “most firms are choosing to proceed with lawyerly caution in the midst of a market that is being reinvented around them.” The key findings from the survey are:

- Unreliable demand

- Surplus of lawyers

- Inefficient delivery of legal services

- Proactivity is a competitive advantage

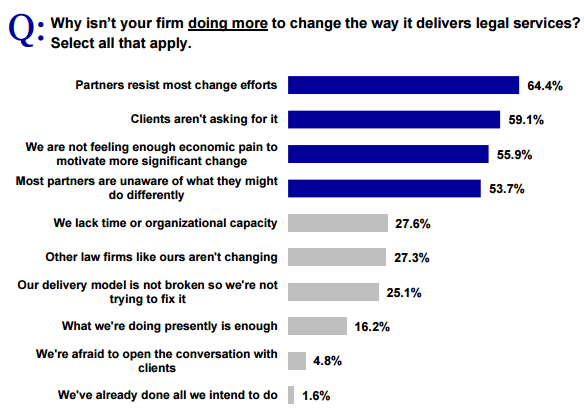

- Resistance to change.

Likewise, the Peer Monitor/Georgetown 2016 Report on the State of the Legal Market states, “U.S. law firms continued to experience very sluggish growth in demand, coupled with negative growth in productivity, and continuing downward pressure on rates and realization.” The Report warns of BigLaw’s Kodak moment:

This story of the demise of Kodak is an important cautionary tale for law firms in the current market environment. Since 2008, the market for law firm services has changed in significant and permanent ways….

The reactions of the law firm market to the rapidly changing environment in which firms operate parallels in some respects the story of Kodak. The current challenge in the legal market is not that firms are unaware of the threat posed to their current business model by the dramatic shift in the demands and expectations of their clients. Instead, as in the case of Kodak, the challenge is that firms are choosing not to act in response to the threat, even though they are fully aware of its ramifications.

There are many reasons that may lead firms to make this choice, but one of the primary ones is surely that, like Kodak, many law firm partners believe they have an economic model that has served them very well over the years and that continues to produce good results today. They are consequently reluctant to adopt any changes that could put that traditional business model at risk. While that might appear to be a viable short-term strategy, the danger is – again like Kodak – that this effort to preserve their past and current success could result in law firms failing to respond to trends that over time could well challenge their traditional market positions.

“Over time.” That’s the thing. There was no single ‘moment’ that caused Kodak’s demise. There was a long series of choices that resulted in Kodak becoming less competitive in the market it once dominated. The market for photography did not collapse. Especially accounting for smart phones and social media, photography is far healthier than it has ever been. But the economics of the market changed, and the largest incumbent did not (enough).

Certainly, advances in technology—from film to digital—underpinned the economic recalibration. But technology was not Kodak’s problem. The Report does a nice job laying out the history in which Kodak itself was responsible for much of the innovation that would undermine its market dominance. Rather, as explained in a new post up at the Harvard Business Review entitled “Kodak’s Downfall Wasn’t About Technology”:

The right lessons from Kodak are subtle. Companies often see the disruptive forces affecting their industry. They frequently divert sufficient resources to participate in emerging markets. Their failure is usually an inability to truly embrace the new business models the disruptive change opens up. Kodak created a digital camera, invested in the technology, and even understood that photos would be shared online. Where they failed was in realizing that online photo sharing was the new business, not just a way to expand the printing business.

The reason we still talk about the “Kodak moment” is that it made for really good copy. Headline writers jumped at the opportunity to use the company’s tagline when describing the rare cataclysm of a premier company filing for bankruptcy. But it was a moment of reckoning that was decades in the making. And the bell was tolling for a once prestigious participant, not the industry itself.

As an industry, legal is doing relatively well. Contrary to the headlines, demand is not flat. Rather, demand for law firm services is flat. According to HBR, the ACC, and LEI, the surplus is being captured by clients and, to a lesser extent (for now), their alternative service providers.

For law firms as a group, the story is one of stagnation, not collapse. There is, however, more volatility at the individual law firm level with bankruptcies and mergers. Unsurprisingly, the volatility is greatest at the individual lawyer and staff level. We’ve experienced significant de-equalizations and layoffs. This year, nearing a decade since the start of the Great Recession, the Am Law 100 again reduced the number of equity partners.

Pretty bleak picture, right? Not really. Not for everyone.

We’re Good

Anyone who is interested in this topic should read Bruce MacEwen’s Growth is Dead and Bruce in general. Among the many reasons to read Bruce is the compelling way he explains that the top lawyers at the top firms have never really experienced a bad year. In the almost three decades (1987-2016) of the Am Law 100, revenues have increased from $7 billion to $83 billion, a compound annual growth rate of 8.9%. Over that time, profits per partner have quintupled (5x) from $324K to $1.6M (2.3x if we adjust for inflation).

And that’s the average firm and the average partner. Averages are misleading. Many firms substantially outperform the average. While at most firms, including the average and below average, the compensation spreads among equity partners keep growing. That is, the people with the most power within law firms have been doing quite well for a long time and there’s no sign of the good times ending anytime soon, for them. Soon matters, of course, because most of them are closer to the end of their career than the beginning. Time horizons affect perspective.

The top partners at the top firms probably figure that clients hire them for their deep expertise. They probably figure clients will continue to do so. Many of them are probably right. And those that are right will continue to have the most power in traditional firms because they will be the ones bringing in the business. The participants with the most interest in shifting the business model—and it is more about business model than tech, which is just one piece—will either not be enfranchised to begin with (e.g. associates and allied professionals with little to zero chance to make partner) or will find themselves disenfranchised (e.g., de-equitization) once the new normal intrudes on their professional tranquility.

Ken Grady recently had some tweets that did a wonderful job summing up partner resistance to change:

Why take risks when you can be rich without doing so? Why try to disrupt yourself when the market is not? If you’ve been extremely successful for 30 years and that is likely to continue for the next 10—when you’ll retire—why change course?

And the explanation need not be avarice. Attention is a finite resource. The most successful lawyers are stunningly busy. They are busy doing important work for key clients. If they are not feeling pressure from those clients (“client’s aren’t asking for it” is the subject for next post) and if market machinations are not affecting their wallets, how much attention are they really going to devote to what appear to be other people’s problemsproblems. How much effort are they going to put into real change, which requires real resources (attention, time, money).

Managing partners are paying rapt attention. Isn’t it their role to force their partners to also come to terms with the shifting market? Call a partners’ meeting. Hand out Bruce’s book and George Beaton’s Remaking Law Firms (both highly recommended). Restructure compensation to tie it more to the firm than individual performance. Invest in infrastructure. AFAs. Legal project management. Technology. Alternative staffing models. Experiment….

That’s all well and good until a few key rainmakers decamp for other firms where they are guaranteed to make more money. Those people who don’t usually pay attention because they don’t have to will still notice if the firm pursues change initiatives that affect their time, workflow, or bank account. On the latter point, supported by strong historical evidence, these successful, high-status professionals consider substantial annual growth in their compensation to lie somewhere between a natural law and a birthright.

Even now, their belief in their ever-escalating economic value seems well founded. The lateral market is nuts. 93.7% of firms are pursuing growth via the zero-sum game of acquiring laterals. Unhappy rainmakers are coveted free agents subject to bidding wars. This makes the BigLaw business model—where your most valuable assets can walk out the door—inherently fragile. Even the largest law firms are susceptible to animal spirits and the cascade effect of rainmaker defections.

The prime directive of the managing partner is to keep the firm solvent and intact. That limits their leverage to force through changes that key partners resist. Successful partners need someone to handle the administrative side of the business. But, as autonomy-seeking missiles, they hate to be managed. Martin Bragg captured this well in exchange we had after my first post on the topic (reprinted with permission):

I am of the view that the real power lies (in most firms) with the king makers rather than the kings which in turn means that (most firms) are herded rather than led. The irony of this is that most lawyers in my experience hate anything to do with firm management but are unwilling to let others do it for them!

As a Martin alludes to, the foregoing is a bit of a caricature. My posts are about “most firms” and are already too long without nuance. There are some managing partners who are empowered to take a “let’em leave” attitude to partner defections. There are large firms with interesting, innovative approaches to business models, R&D, and productizing services. It’s not that change isn’t happening. It just doesn’t seem to be happening enough.

I’ll leave the final word to Bruce, who had a great post reacting to the Global 100:

In Law Land the cynical smart money is almost always on stasis; nothing will really change because any talk otherwise will spook the partners. If nothing else, this view has years and years of solid predictive success behind it.

But I wonder.

Rates of growth and decline—I emphasize decline because it is largely a story of decline in the only currency that matters, purchasing power—in overall gross revenue, RPL, PPL, and even PEP are to almost all of the 120,000+ lawyers toiling in these firms pretty abstract and denatured concepts.

One number, however, is as hard core and riveting as can be: One’s own personal compensation. This is where the abstracted figures have an impact people recognize and understand.

We can all have a debate in the parlor about whether too many lawyers with room temperature C+/B- talent were too highly paid by too many firms for too long, but as the reality of these numbers, “the New Normal” as far as the eye can see, and heaven only knows what other exogenous shocks intrude on our world, begin to sink in, real take-home pay is going to fall, and barring “something radical,” continue to fall for the great majority of these 120,000+ souls. (You guys gathered under the Wachtell banner, and few others of similar caliber, are excused—but then I stipulated I’m talking about C+/B- talent, so you knew that already.)

Upton Sinclair (1878—1968) was among many other things , author of the 1906 classic The Jungle, exposing malfeasance in the US meat packing industry and contributing to momentum behind passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act. He also gets credit for this barbed quip:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.

For quite some time now—coming up upon a decade—for partners in highly successful firms to “understand” that the good old days aren’t about to return would have entailed their understanding that the ever-upward trajectory of their compensation could be imperiled. No wonder the notion of change, much less “something radical,” spooked them. Self-interest required no less.

What if that is something that might be about to change?

Author

D. Casey Flaherty founded Procertas, a new kind of company for an evolving legal marketplace:

D. Casey Flaherty founded Procertas, a new kind of company for an evolving legal marketplace:

“Our mission is better alignment between law firms and law departments, as well as between law departments and the businesses they represent. Our flagship product, the Legal Technology Assessment (LTA), improves quality and increases efficiency by ensuring that legal professionals are properly using the basic technology tools of their trade: Word, Excel, and PDF. The LTA is a first-of-its kind integrated benchmarking and training platform pairing competence-based assessments with synchronous, active learning in a completely live environment. Our clients become COBOT Qualified (Certified Operator of Basic Office Technology).”

BTW, Procertas stands for Professional Certifications and Technology Assessments.

Law Firm Partners: If It Ain’t Broke…was first published on 3 Geeks and a Law Blog on July 24, 2016 and is reproduced on Dialogue with permission from D. Casey Flaherty, one of our regular contributors.

“…an economic model that has served them very well over the years and that continues to produce good results today. They are consequently reluctant to adopt any changes that could put that traditional business model at risk.”

This is the foundational premise of “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” Clayton Christenson’s (1997 Ed.) book about the difficult choice between supporting one’s current Golden Goose and gutting it in preparation for a very different future.

It can be done, though, as former IBM CEO Lou Gerstner showed in “Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?” which sums up his historic business achievement, bringing IBM back from the brink of insolvency to lead the computer business once again. He did so by abandoning the mainframe cash cow in favor of services.

IBM is a pretty good metaphor for BigLaw: Long-established, respected brand, market leader, the “safe choice” for many buyers, hugely profitable at its apex, but on a long, slippery slope. Not a precipice, but definitely a downward slope.